The voice of the sea speaks to the soul.

–The Awakening, Kate Chopin (1850-1904)

❀ ❀ ❀ ❀ ❀

For me, the highlight of any beach trip is walking the strandlines, and exploring the tide pools; something I’ve been enjoying since I was old enough to walk. One time up north, in the charming town of Coupeville on Whidbey Island, Washington, was a tiny beach. Along the strandline were shells, urchins, and seaweeds, and a colorful display of sea stars on the pilings. The urchins were a nice find, as they are not at all common on Oregon beaches. But what I considered the best find, was the baby shark that had washed ashore. I doubt it had been dead long, for it was fully intact, and looked like it could come alive at any moment. Its body gleamed a silvery-gray. Its mouth, slightly ajar, revealed rows of sharp, pearly white teeth. Only a foot and a half long, it wasn’t much bigger than those rubber toy white sharks sold in gift shops along the coast.

Another time, farther south, in Seaside, Oregon, I found a small metal box on the beach. It was secured to a barnacle-covered rock (about the size of a bowling ball) and packed in wet sand. The metal box had no lid and was filled with seawater, sand, and barnacles. If there had been a treasure inside, it was gone now. Or was it? Something bright caught my eye; shades of ruby, sapphire, amethyst, emerald, and gold. They were the vibrant colors worn by a small sea creature—a shell-less, slug-like mollusk called a nudibranch. There are approximately 200 species of nudibranchs in the Pacific Northwest; most are decorative and colorful, living works of art; some are smooth, some wear ruffles, and others sport soft tubular-like hairs like the one I had found. Being deep-water creatures, it’s rare to find them along the beach. And, oh, what a thrill of finding such a wonderful, living treasure!

Strandlines are delightful, for one never knows what the tide will wash in. Such was the time when I was combing the sands in Cannon Beach, Oregon. I’d come upon an ocean sunfish, the Mola mola; a large, deep-sea, flat fish that’s often described as simply a fish that is all “head and tail.” It is an odd, but amazing looking creature. The ocean sunfish will often bask on the surface, where it will leisurely drift for miles. It is the heaviest “bony” fish in the world. Adults can weigh as much as 1,000 pounds. The largest ocean sunfish ever caught was in 1910 that weighed 3,500 pounds! Sometimes, they wash ashore during storms, as the one I found most likely did. It measured nearly three feet in diameter, a remarkable find indeed; what’s more, it hadn’t been dead long, and was completely intact, for the gulls had not yet found it.

(I only wish I had pictures of these earlier finds to share with you, but unfortunately, it was before the digital age.)

The Strandline . . .

❀ ❀ Strandlines are fun, but when the tide recedes, it’s time to go tide pooling! ❀ ❀

The Tide Pools . . .

Tide pools hold seawater, and are exposed at low tide. Life in the tide pools isn’t easy. Plants take a beating from heavy surf and strong currents. Animals hunt and are hunted. These pools are a vital habitat for many marine plants and animals that could not survive without them.

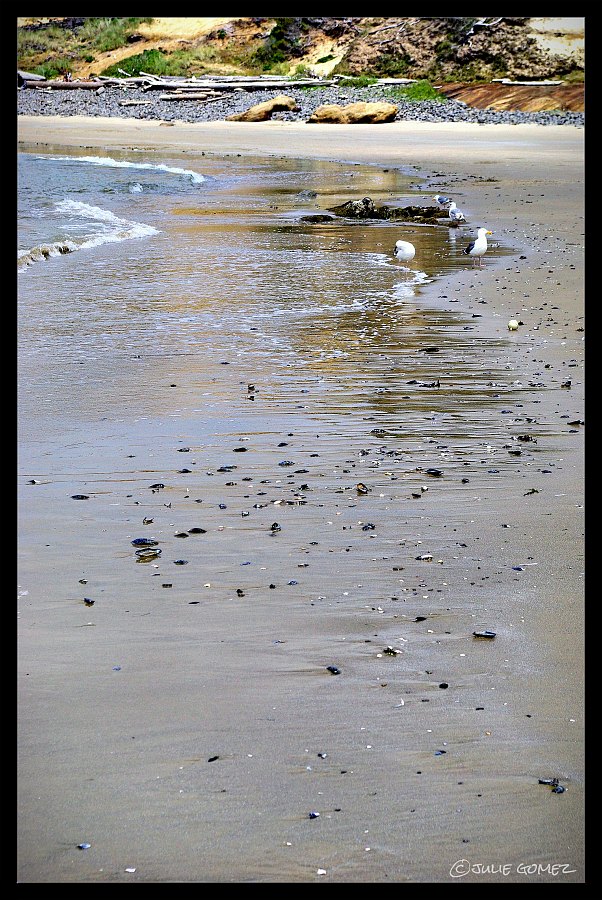

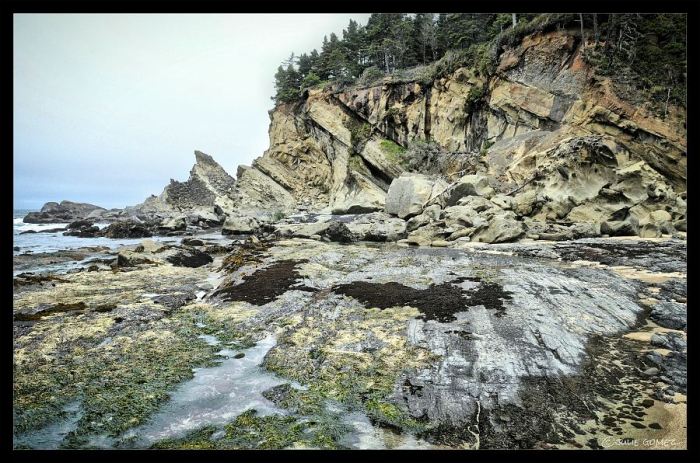

This past summer, while along the southern Oregon Coast, my husband and I hiked to Simpson Beach. Our timing was right for a change, and the tide was very low when we reached the beach. A small beach, it was crammed with small tide pools. But what these tide pools lacked in size, they made up for with exciting plants and animals; some of these finds were first time sightings for me. There was a lot to see. I wasted no time. I was like a child again, touching everything in the tide pools within my reach, and loved it! I was careful where I walked. Never had I seen so many turban snails. There were also whelks of assorted colors and patterns. There were rock-boring snails, rock crabs, sea sculpins, blue mussels, barnacles, and green anemones . . .

In and around the tide pools of the intertidal zone, an area exposed during the lowest tide, was mossy chiton (Mopalia muscosa). These living fossils are so well camouflaged they nearly had me fooled thinking they were part of the rock themselves. But once my eyes adjusted, I found dozens. The mossy chiton is a blind mollusk with a vulnerable underside. Its only protection is the dorsal shell, hard outer plates that have eight segments that allow the chiton to flex. The dorsal shell is black when wet; when dry, it is light gray. When not covered with barnacles, these plates feel as smooth as polished stone. To complete its disguise, the outer area of the dorsal plate, called a girdle, is fringed with stiff, moss-like hairs. Mossy chitons travel and feed at night, and only when submerged in seawater. As it forages, it moves slowly using its strong muscular foot that it also uses to anchor itself to rocks. As it moves, it feeds on microscopic red and/or green algae that it scrapes from the rocks with its abrasive, leathery, strap-like tongue called a radula. This was a first sighting for me, and my second chiton species; it was an exciting find.

Lastly, not all tide pool discoveries are animals; often times there are sea plants. A sea plant that puzzled me for years, and one that I have only recently come to know, is coralline algae that belongs to the genus Bossiella. It absorbs calcium carbonate from seawater, a natural, and insoluble solid that form hard corals and mollusk shells. In life, coralline algae generate dense colonies in the tide pools where they provide rich habitat for snails, hermit crabs, sculpins, chitons, and other life forms. In death, its limbs don’t wilt, but instead they calcify beautifully, turning brittle and as white as bone. In the end, the calcified carbonate is ultimately crushed by surf and dissolved by seawater.

I leave the tide pools a little wiser, and with more questions than answers. That’s fine! I love a good mystery. It’s what keeps me coming back.

____________________

Thank you for visiting!

Copyright 2014. All rights reserved.